How Bottle Bills Reduce Waste and Support the Circular Economy

Bottle bills – or, as they’re often called, deposit-refund systems – are behavior-rewarding incentive initiatives that are proven, effective approaches for recovering containers for reusing, refilling, or recycling.

You’ve probably seen to a grocery store with an area to return used beverage bottles and cans. When you first bought your beverage, you were charged a deposit. And when you come back to the store, you bring your empty bottles and cans, which are either fed to a return machine or dropped off in a bag with an RFID sticker tied to your account.

With each bottle or can returned, you get a monetary credit added to your refund. When finished, the machine prints a receipt with the refund total, which you can then turn in for cash or use towards your next shopping trip.

This is a deposit-refund system in action, and right now, these systems are only found in certain states.

But have you ever wondered what’s the history behind these systems, and how do they contribute to less waste in the long run? Let’s take a closer look.

The Good Old Days of Return and Refill

Human societies and businesses have been using deposit-refund systems since the dawn of civilization. Before the modern era, if you wanted to buy a consumable product, you would either bring your own container to be filled at the store or market, or the merchant would sell their product in a refillable container that they would loan or rent to you.

When you were done, you would bring it back (or it would get picked up) and the merchant would wash it and refill it again for another customer. To ensure that they got their packaging back, merchants would charge their customers a deposit at initial purchase, which was refunded when the customer brought the container back.

Back then, materials like glass, ceramics and metals were seen to have value. Businesses and consumers wanted to use them for as long as possible.

Companies like Coca-Cola and Budweiser popularized mass-market deposit-refund systems in the late 1800s. <old Coca-Cola or Budweiser logos or product images> Soda and beer companies had distribution hubs where they would take back refillable glass bottles for washing and refilling.

The infrastructure allowed virtually all commercial beverages sold in the United States to be sold in refillable bottles.

The Big, Disposable Idea

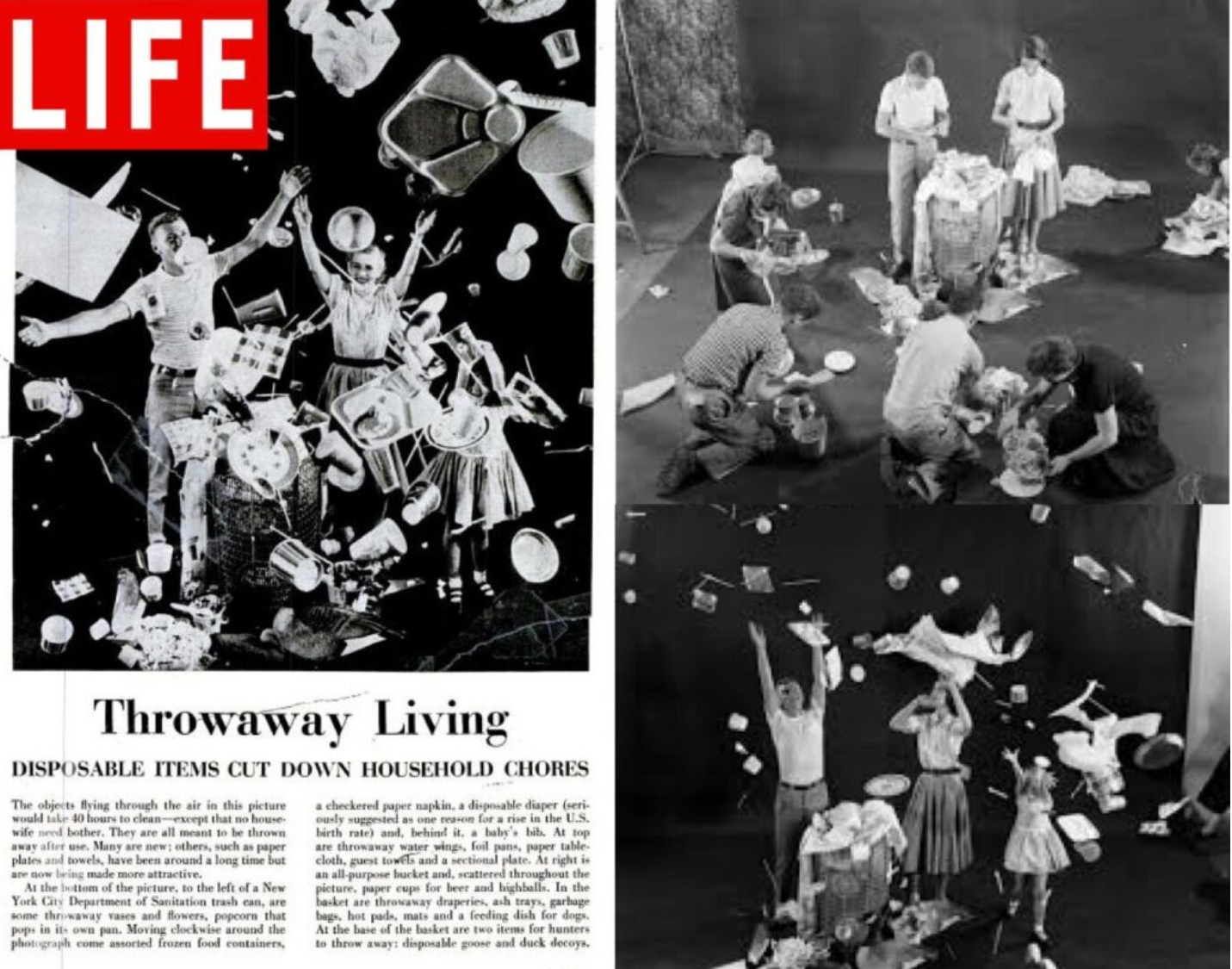

Unfortunately, things changed after World World II. During the war, the extraction, mining and manufacturing industries ramped up production levels to serve the war effort. Business was good – but once the war was over, they asked, “What should we do now?”

Their answer: Keep churning all these materials through the economy. One of the big ideas was to sell these materials – like aluminum, paper, and eventually plastic – in the form of disposable products.

The Start of the Throw-Away System

Extraction companies began to develop partnerships with consumer goods and beverage companies. Big soda and beer companies shifted their packaging away from refillable glass to disposable aluminum, glass and plastic containers for soft drinks and other non-alcoholic beverages.

Environmental Repercussions

Not surprisingly, beverage containers ended up in the environment as litter.

The explosion of litter provoked the ire of concerned citizens and policymakers. Leading up to the first Earth Day in 1970, environmental demonstrations across the country focused on the issue of throwaway containers.

These protests held the industry — not consumers — responsible for the proliferation of disposable items that depleted natural resources and created massive amounts of litter. Originally billed as a litter prevention tool, legislators also developed and introduced what we now call “bottle bills”: mandatory deposit-refund systems that require beverage companies to take their bottles back for reuse or recycling, and to ensure that they wouldn’t be littered.

But the beer and soda industries, as well as the aluminum, glass and plastics companies – who were making all kinds of money selling one-way containers – pushed back.

“Bottle Bills are mandatory deposit-refund systems that require beverage companies to take their bottles back for reuse or recycling.”

The Problem with the “Crying Indian”

The Chicago Tribune artfully documents the industry pushback in their 2017 research piece, “The ‘Crying Indian’ ad that fooled the environmental movement.”

Major players in these industries founded an organization called Keep America Beautiful, which ran advertising campaigns to convince the American public that litter was a people problem, not an industry problem.

The most memorable of these ads was the Crying Indian commercial. It featured Iron Eyes Cody, an Italian-American actor in Native American garb, who paddles a birch bark canoe on water that seems tranquil and pristine but becomes increasingly polluted along his journey. He pulls his boat ashore and walks toward a bustling freeway. As he looks at the polluted landscape, a passenger hurls a paper bag out a car window. The bag bursts on the ground, scattering fast-food wrappers all over his beaded moccasins.

The camera zooms in on Iron Eyes Cody’s face to reveal a single tear falling down his cheek. At the moment the tear appears, the narrator, in a baritone voice, says: “People start pollution. People can stop it.”

As the Tribune reports, Keep America Beautiful was practicing a sly form of propaganda. Since the corporations behind the campaign never publicized their involvement, people assumed that the group was a disinterested party.

By making individual viewers feel guilty and responsible for pollution, the ad deflected responsibility away from corporations and placed it entirely on individuals, concealing the role of industry in polluting the landscape.

“The ad deflected responsibility away from corporations and placed it entirely on individuals, concealing the role of industry in polluting the landscape.”

The Lesser of Two Solutions

While environmental advocates eventually succeeded in passing bottle bills in 10 states, the soda, bottled water and beer industries prevented their expansion elsewhere. Instead, these industries focused on promoting government-run and paid-for recycling programs.

Although these government programs have helped increase recycling in the US, they haven’t put a dent in litter. In addition, they caused recyclable materials to be degraded and either downcycled into lower value products or landfilled instead of actually being recycled.

Good News for Circularity

Nevertheless, after 40+ years of fighting bottle bills in the US (and around the globe), big soda and bottled water have recently shifted their position to tentatively support them.

Many of these companies are tired of being the world’s worst plastic polluters and recognize the need to do something about it. And recent changes in leadership are bringing in a new generation who have different ideas, values and priorities.

What’s even better, is that industry support for deposits has opened up a conversation on reuse and refill provisions and targets that would not have happened otherwise. These targets work like fuel efficiency standards for cars, which apply to each individual auto-maker so they meet a miles per gallon standard across the cars they sell each year.

Similarly, refill targets would apply to each individual beverage company, and they would have to sell a certain percentage of their products in refillable containers by a certain date, starting smaller and adjusting higher over time. And now, Upstream is working with them on national legislation to set up bottle bills in every state.

“Refill targets would apply to each individual beverage company, and they would have to sell a certain percentage of their products in refillable containers by a certain date.”

The Bottle Bill Vision

We already know that bottle bills are the most effective tool to prevent plastic pollution caused by soda and water bottles (and litter from beverage containers overall), which currently make up 40% to 60% of roadside litter in non-deposit states.

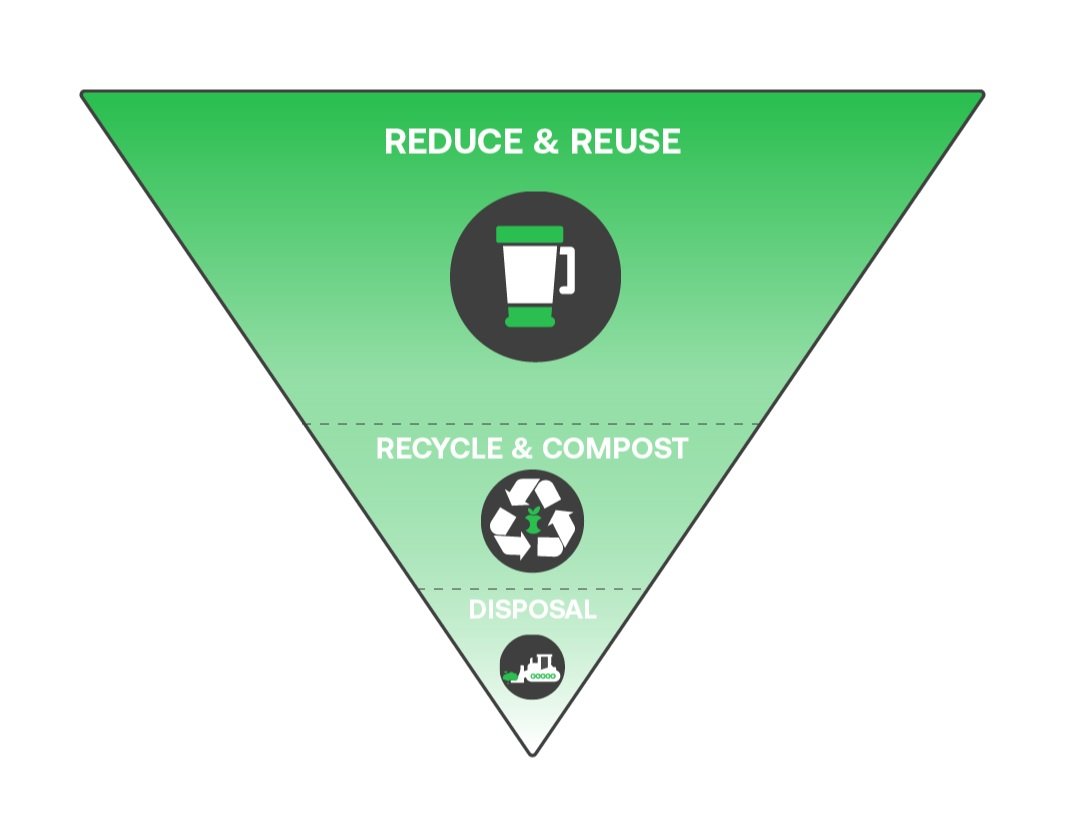

But our long-term vision is that the bottle bill becomes a tool to achieve the waste reduction hierarchy – reduce and reuse before recycling – and that today’s high recycling rates instead become high reuse and refill rates.

From there, the transformation to a truly waste-free world can begin in every American household.