Circularity Infrastructure and Procurement: Tools for a Just Transition

By Yinka N. Bode-George, Founder and CEO of Sustain Our Future Foundation

Part of Upstream’s series examining the principles of a just transition and how reuse is in conversation with every element.

An illegal dumping site in a Baltimore Neighborhood.

As a young researcher and resident in Baltimore City, I spent time in West Baltimore neighborhoods where, for years, a children’s mural declared, “ur mess is our stress.” The image showed a piece of trash missing a bin.

In neighborhoods like Franklin Square and Harlem Park, residents were living with the long afterlives of redlining, disinvestment, inadequate sanitation services, illegal dumping, and vacant housing — a national phenomenon first highlighted in the 1987 United Church of Christ report Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States, which found race to be the primary predictor of the location of commercial hazardous waste facilities across the country. In Baltimore, waste accumulated not just in streets and alleys, but in vacant lots, abandoned buildings, and public spaces where basic public infrastructure had frayed.

Residents described carrying garbage in their handbags because there were no public receptacles, organizing cleanups with just a handful of remaining neighbors, and navigating bureaucratic systems that reported problems “resolved” while mounds of waste remained on street corners.

The burden was not only physical. It was psychological. People spoke about stress, exhaustion, and the normalization of environmental disorder. How living among trash, pests, and neglected land subtly communicates that a place, and the people in it, are disposable. At the same time, residents resisted being treated as a dumping ground. They questioned why their neighborhoods were sites for neglect, illegal dumping, and sometimes even externally driven “green” projects that arrived with good intentions but little accountability, local power, or long-term care.

What I came to understand is that waste is not just a materials problem. It is a governance problem, a social problem, and an infrastructure problem. These conditions were not accidental; they were built through policy decisions, investment patterns, and whose needs were prioritized or ignored.

Today, as the circular economy gains traction as a climate solution, we stand at a similar crossroads. Circularity is often framed as a technical shift: reduce waste, increase recycling, design for reuse. But if we only redesign materials flows without redesigning who holds power, capital, and infrastructure, we risk rebuilding a circular version of the same extractive economy.

A just transition asks a deeper question: as we move away from wasteful, polluting systems, who gets to build what comes next, and who benefits?

At Sustain Our Future Foundation (SOFF), our work sits at that intersection. We focus on embedding equitable community benefits directly into large-scale sustainability and infrastructure efforts. Increasingly, that means working with corporations that have circularity and zero-waste commitments and helping translate those commitments into community-rooted circular infrastructure.

One promising mechanism for doing this is the Circular Solutions Agreement.

“Circularity is often framed as a technical shift: reduce waste, increase recycling, design for reuse. But if we only redesign materials flows without redesigning who holds power, capital, and infrastructure, we risk rebuilding a circular version of the same extractive economy.”

From Renewable Energy PPAs to Circular Solutions Agreements

Imagining Circular Solutions Agreements means learning from existing agreement models. Over the past decade, corporations have used long-term energy offtake agreements, such as power purchase agreements (PPAs), to accelerate renewable energy development and support their clean energy commitments. By committing in advance to purchase electricity from renewable projects, companies helped unlock financing for infrastructure that might otherwise not have been built. PPAs became a powerful tool for corporate energy procurement while also driving broader energy grid decarbonization. This approach is also being leveraged as a model for other kinds of sustainable procurement, such as carbon removal offtakes like carbon removal units.

Importantly, some PPA innovations have gone beyond energy sourcing alone. Models such as Microsoft’s PPAs include community benefit provisions. These models have demonstrated how renewable energy procurement can also resource local priorities by directing a portion of project financing toward climate resilience measures, residential energy efficiency for working families, support for emerging sustainability enterprises, and workforce development programs for communities navigating economic transition, including farmworkers and fossil fuel–dependent workers.

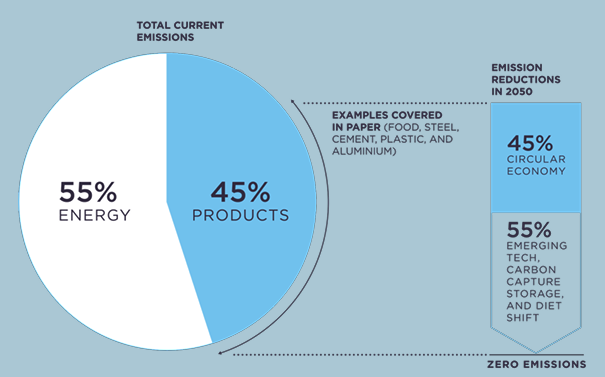

Ellen MacArthur Foundation

The key insight is that procurement structures can be designed not only to buy a commodity, but to shape how infrastructure benefits people and places.

Circularity now faces a parallel challenge. According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, while 55% of global greenhouse gas emissions are tied to energy use, approximately 45% are attributed to the production of materials and the management of land, including landfilling and waste incineration. Advancing circular solutions, particularly across industrial materials and food systems, is therefore a critical component of climate action.

Yet, global material circularity remains only about 6.9%, according to the 2025 Circularity Gap Report. Many reuse, repair, remanufacturing, composting, and materials recovery solutions struggle to scale due to uncertain demand, risk-averse markets, and persistent underinvestment in distributed circular infrastructure. At the same time, communities that have long borne the burdens of waste, pollution, and industrial siting are often left out of ownership, decision-making, and economic participation in the emerging “green” economy.

Similar to renewable energy procurement, corporate circularity procurement offers a potential pathway forward if structured intentionally.

The Circular Solutions Agreement adapts the forward-procurement logic of PPAs to the circular economy. Through long-term service or offtake commitments, companies can help anchor:

Materials recovery and reverse logistics systems

Reuse and repair networks

Remanufacturing facilities

Low-carbon production using recovered materials

Composting and organics processing hubs

However, infrastructure investment alone does not guarantee tangible benefits for communities historically positioned at the margins of economic systems. Without deliberate design, circular procurement can simply channel new value through old inequitable structures. The structure of the transaction matters. This is where SOFF’s community benefits agreement model becomes essential in aligning circular procurement with mechanisms that improve material conditions for communities, not just materials flows within supply chains.

Sustain Our Future Foundation's community benefits agreement model aligns circular procurement with mechanisms that improve “material conditions” for communities, not just “materials flows” within supply chains.

When Circular Solutions are Designed With Communities

Across the country, there are already examples of circular and reuse collaborations between companies and communities that keep materials in motion while responding to community-defined needs and building local economic prosperity. What distinguishes these projects is not just what they do, but how they are developed: through partnership, local relevance, and shared benefit.

The FedEx and ERS Case Study: Electronics Reuse as Workforce and Supply Chain Infrastructure

One model, piloted by FedEx, centers the electronics sector and connects device reuse with inclusive workforce development and domestic materials recovery.

Through a device take-back pilot initiative, individuals and businesses across Nashville, Tennessee were able to mail in used electronics using FedEx logistics. This streamlined system made responsible device return accessible at scale, while certified recycling processes ensured secure data handling and environmental compliance.

Repairable devices were directed to Electronics Recycling Solutions (ERS), a Nashville-based social enterprise specializing in electronics repair and refurbishment. ERS integrates workforce development into its operations by providing training and employment pathways for adults with developmental disabilities, directly linking e-waste reduction with inclusive job access and skills-building in high-demand technical fields.

Devices that could not be repaired were responsibly disassembled, with components such as lithium-ion batteries entering domestic secondary materials supply chains that support clean energy manufacturing and battery recovery.

In this model, corporate logistics infrastructure, community-based enterprise, and secondary materials markets operate as parts of one circular system. Reuse functions simultaneously as climate action, workforce strategy, and supply chain development.

The Zero Waste Westside Atlanta Case Study: Composting, Food Systems, and Corporate Partnerships

Zero Waste Atlanta

A second example from Atlanta’s Westside shows how circular solutions can be rooted in local food systems and environmental education.

Goodr, Truly Living Well, and Green Is Lyf formed Zero Waste Westside to help residents understand everyday waste while building local composting systems and reducing food waste sent to landfills. Each organization brought a distinct role: food recovery, compost processing and urban farming, and community outreach and education.

Support from Microsoft, connected to plans for a new Atlanta campus in the Westside, provided catalytic funding that allowed these community-rooted organizations to align their work and expand neighborhood-level impact. Even though the larger campus buildout was ultimately paused, the collaboration demonstrated how a local community farm could function as a compost collection and processing hub for a corporate entity.

Rather than relying exclusively on distant, industrial-scale facilities, circular systems were embedded within neighborhood food, soil, and education infrastructure. In this case, circularity intersected with local food system resilience, soil regeneration, community education, and neighborhood-scale environmental infrastructure.

Together, these examples show what becomes possible when companies move beyond transactional waste services and begin partnering with community-rooted organizations around circular solutions with social, environmental, and economic relevance.

Scaling Community-based Circularity Solutions

The examples above show what is possible, but too often, these efforts depend on extraordinary local leadership, short-term grants, or one-off partnerships. They demonstrate innovation, but remain difficult to scale.

To scale community-based solutions, the right structure is crucial.

Many community-rooted circular enterprises — including reuse and repair hubs, composting operations, community-led materials recovery facilities, and remanufacturing initiatives — are closest to community priorities but farthest from capital and large-scale procurement pathways. They often lack the upfront resources needed for equipment, certifications, staffing, facility upgrades, and systems required to meet corporate contracting standards.

Without that pre-development support, companies frequently default to large incumbent service providers, even when community-based suppliers are better aligned with just transition goals. Bridging this gap requires aligning procurement, philanthropy, and community benefit design as parts of one system rather than separate efforts.

Sustain Our Future Foundation operates as a nonprofit intermediary embedding justice-driven capital strategies inside large-scale sustainability and infrastructure efforts. In the circular economy context, this means supporting the conditions that allow community-rooted circular enterprises to become viable partners in corporate supply chains.

Last fall, SOFF directed grant funding to a cohort of circularity-focused organizations working at the intersection of pollution reduction, zero waste, and community-rooted economic development, including: Glass Recovery and Sustainable Systems (GRASS) in Baltimore; Valley Improvement Projects in California’s Northern San Joaquin Valley; Pocasset Pokanoket Land Trust in Rhode Island and Connecticut; the Black Fiber and Textile Network; Human-I-T; and Eureka Recycling in Minnesota.

These grants functioned as pre-development and operating capital, helping organizations strengthen infrastructure, workforce capacity, systems, and operational readiness in ways that position them for deeper participation in circular supply chains. In this sense, philanthropy operates as catalytic capital, helping community-based enterprises move from under-resourced local actors to potential suppliers and long-term partners.

Importantly, this grantmaking was made possible through a renewable energy community benefit collaboration. This approach demonstrates how infrastructure transactions can be structured to generate flexible funding streams for long-term community capacity building, which is essential for accountability and harm reduction. Dedicating a portion of resources as flexible funding towards workforce pathways, small enterprise development, and community-rooted infrastructure helps build the conditions for durable community participation in the emerging green economy.

The same logic can extend to circularity. As companies invest in renewable energy, facilities, logistics networks, and other large-scale infrastructure, there is an opportunity to intentionally design community benefit approaches that include:

Community benefit funds

Catalytic philanthropic capital targeted at local circular enterprises

Capacity-building support that prepares community-based organizations to engage as suppliers and partners

Together, these elements begin to form a just transition finance stack:

Corporate Procurement: Creates predictable demand and can provide financing for initial development costs through forward offtake agreements.

Community Benefit Structures: Can direct holistic resources toward local priorities for durable community-based enterprise participation.

Philanthropic Grants: Can provide catalytic capital and support the maturation of community-rooted suppliers.

“This approach demonstrates how infrastructure transactions can be structured to generate flexible funding streams for long-term community capacity building, which is essential for accountability and harm reduction. Dedicating a portion of resources as flexible funding towards workforce pathways, small enterprise development, and community-rooted infrastructure helps build the conditions for durable community participation in the emerging green economy. ”

Building What Comes Next

In neighborhoods like those I lived in and studied years ago in West Baltimore, waste was never just about what people threw away. It was about who was expected to live with neglect, who carried the burden of broken systems, and who had little say in what infrastructure entered their communities in the name of improvement.

As we build the circular economy, we have a choice. We can treat circularity as a technical upgrade to existing waste systems: cleaner and more efficient, but governed by the same inequitable patterns. Or we can treat it as an opportunity to redesign infrastructure, contracts, and capital flows so that communities historically positioned as dumping grounds become partners, decision-makers, and beneficiaries.

Reuse and circularity are critical infrastructure systems. They require logistics networks, facilities, workforce pathways, financing structures, and long-term institutional commitments. When designed intentionally, these systems can reduce pollution and emissions while also strengthening local economies and supporting community-rooted enterprises.

Companies with circularity and zero-waste goals can begin now by:

Exploring long-term procurement models, such as Circular Solutions Agreements, that help anchor distributed circular infrastructure

Partnering with intermediaries to identify and support community-rooted suppliers

Pairing procurement with community benefit and catalytic funding approaches that build local capacity, not just extract services

Producer Responsibility Organizations (PROs) formed under extended producer responsibility (EPR) laws also have a role to play in this ecosystem. By directing producer fees toward community-rooted circular enterprises and distributed infrastructure, EPR can be a strong lever for building more locally accountable and equitable circular economies.

The question is not only how to keep materials in circulation. It is how to ensure the systems replacing the linear economy repair, rather than repeat, the patterns that produced environmental harm and inequity in the first place.

That is the work of a just transition in the circular economy. And, it starts with how we design the infrastructure of circularity.

“As we build the circular economy, we have a choice. We can treat circularity as a technical upgrade to existing waste systems: cleaner and more efficient, but governed by the same inequitable patterns. Or we can treat it as an opportunity to redesign infrastructure, contracts, and capital flows so that communities historically positioned as dumping grounds become partners, decision-makers, and beneficiaries.”

Yinka N. Bode-George is the Founder and CEO of Sustain Our Future Foundation, a national nonprofit organization. She collaborates with corporate sustainability teams, and developers, to build community benefit strategies within energy and infrastructure projects. Yinka's work translates corporate sustainability commitments into durable, place-based resources that advance responsible development, shared value, and community agency.